Will AI hit employment, raise productivity, and increase inequality?

The release of ChatGPT in November 2022 has raised great hopes that artificial intelligence (AI) can contribute to solving problems in many fields and lift productivity, but also fears that many jobs may disappear, and that income inequality could rise further. AI is commonly seen as a general-purpose technology, like the internal combustion engine, early electricity-based technologies, and computers. Such technologies have the potential to disrupt large parts of the economy, displacing many workers. Every wave of innovation in history has generated fears of “technological unemployment” but so far economies have generally succeeded in creating more jobs than those that were destroyed, even though transition phases have often been painful.

Automation generally leads to productivity gains, which generate income that can be spent on new products and services, which in turn creates demand for labour. Employment in difficult to automate activities rises with aggregate demand and new occupations are being created. David Autor, from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and co-authors, find that about 60% of 2018 US jobs did not exist in 1940. Reallocation of labour associated with technological change challenges workers, who often need reskilling and upskilling. Structural change may also be associated with macroeconomic and financial instability if economies struggle to adapt. The income distribution is affected, as illustrated by the polarisation of labour markets in many advanced economies over the past decades.

Will labour market developments in the AI era follow historical patterns, or will AI be a game changer? Like many digital tools before it, AI offers large potential for deployment across a wide range of economic activities. Until recently, mainly routine tasks could be automated. AI offers possibilities to automate non-routine cognitive tasks, thanks to its ability to learn by itself from huge datasets and integrate tacit knowledge. Some researchers believe that machines could ultimately outperform humans in almost all activities. Nevertheless, even if one believes such prophecies, they are probably far away in the future. At the current juncture, AI can automate some cognitive tasks and complement humans in performing more complex ones.

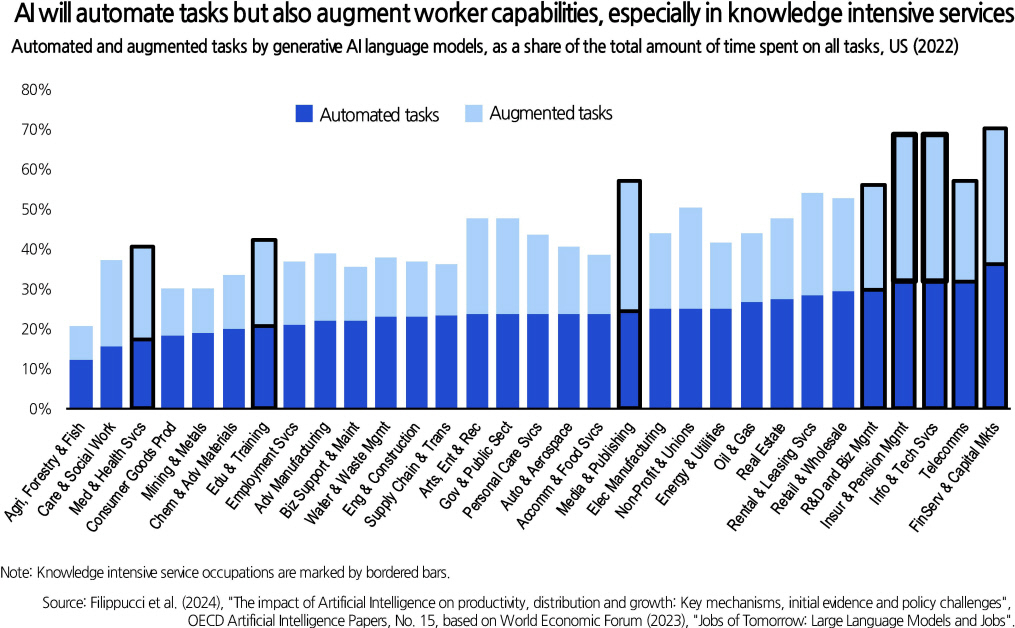

Several studies have investigated different occupations‘ exposure to AI, by linking some AI applications to skills used in specific professions. This is a good starting point for thinking about the potential impact of AI on jobs, productivity, and inequality. Research from the OECD Global Forum on Productivity suggests that jobs in knowledge-intensive services, such as finance, advertising, consulting, and information and communication are the most likely to be affected by AI. Conversely, workers in industries like mining and construction, or relatively low knowledge-intensity services, such as administration and support, transportation, and water and waste, have limited exposure to AI. This has prompted fears that technological development, after automating routine tasks, which affected mainly blue-collar workers, would go on to automate even knowledge-intensive tasks, threatening the jobs of high-skilled workers.

| ||

| Since 2000, some 1.7 million manufacturing jobs have already been lost to robots. Up to 20 million manufacturing jobs will be lost globally to robots by 2030, a new study has found.[REUTERS] |

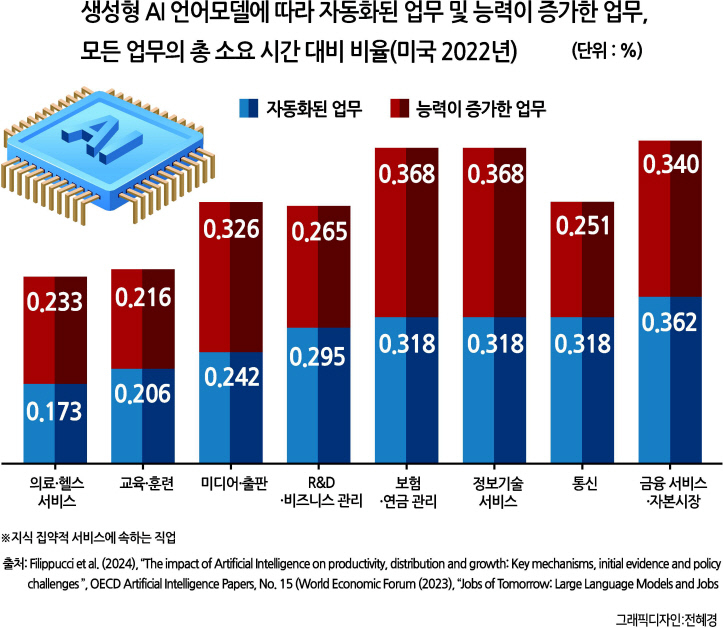

A crucial question is whether AI can mainly automate tasks or whether it also has potential to augment workers‘ abilities to perform their jobs. In other words, whether AI is mostly a substitute or a complement to human labour. According to a World Economic Forum report, both aspects are important, and their strength varies across economic sectors. Tasks are considered automatable if they do not require creatively solving ambiguous problems, working with others in real time or validating outputs. The potential for augmentation of worker capabilities is particularly high in knowledge-intensity services. For example, in information and technology services, nearly 32% of the time spent on all tasks could be subject to automation, but the potential for augmentation is even higher, reaching almost 37% of the time spent on all tasks. In media and publishing, the potential for augmentation dominates that of automation even more, at 32% versus 24% of the time spent on all tasks. Hence, while AI is likely to displace some workers, it will also boost the productivity of others. To give more concrete examples, while AI can improve medical diagnosis and help build legal cases, it is unlikely to replace physicians and lawyers anytime soon. AI provides skilled professionals with new valuable tools, but in many circumstances, human intervention is still necessary, especially in high-stakes decisions, not least because AI is sometimes subject to hallucinations, producing inaccurate or misleading results.

Recent studies point to significant improvements in workers‘ performance due to AI in some specific tasks, ranging from 14% in customer services to 56% in coding. This suggests that if AI were to be widely adopted across the economy, productivity may rise substantially. However, translating micro-level performance into economy-wide productivity is challenging. Estimates of AI’s potential labour productivity boost over the next decade in advanced economies generally vary from about 0.1 to more than 2.5 percentage points per year. To put these numbers into perspective, US nonfarm labour productivity grew at an average annual rate of 2.1% between 1947 and 2023, and 1.5% since 2006. Hence, according to the most optimistic estimates, AI would lift productivity growth well-above historical trends. Median estimates would bring labour productivity growth close the 3% observed between 1996 to 2005, during the deployment of the internet. However, other studies suggest this may be too optimistic. AI-related productivity gains are likely to vary across countries. Korea is well placed to be among the main beneficiaries, thanks to its high level of digital development and strong position in the global semiconductor market.

AI‘s productivity effects will partly hinge on the degree and speed of AI adoption, which in turn will depend on costs, as well as the ability to mobilise complementary factors and rethink production processes and business models. AI models are expensive to develop, but applications are also often costly to run. AI’s high energy consumption may threaten sustainability objectives. Deployment may also be constrained by bottlenecks in complementary factors, such as data and skills. OECD research has documented a widening productivity gap between frontier firms and other companies over the past two decades, which AI may widen further if big tech companies can leverage access to data, skills, and computing power to further entrench their digital markets dominance. Thus, monitoring AI competition will be essential to foster innovation and productivity growth.

| ||

| AI is taking over job hiring. Job applications are increasingly being screened by algorithms built to automatically flag attractive applicants to hiring managers.[AFP] |

While many economists expect the adoption of AI to bring a gradual shift in productivity levels over the coming decade, the most optimistic anticipate a permanent increase in productivity growth rates, resulting from accelerated progress in research. Such optimism is partly grounded in the success of some AI applications addressing bottlenecks in research processes. For example, an AI system was able to predict a protein‘s 3D structure from its amino acid sequence, opening great prospects for biology and medicine. However, historically, technological progress has tended to come in waves, despite the emergence of ever more powerful research tools. Furthermore, the translation of scientific discoveries into economic applications is never straightforward and is often contingent on factors beyond technology.

Altogether, both fears of large-scale job destruction and hopes of a huge boost to productivity growth seem overblown at this stage of AI development. Nevertheless, AI will transform the way we work, affect business models, and have distributional consequences. Recent studies suggest that AI adoption may reduce wage inequality within professions, as AI seems to raise the productivity of inexperienced workers disproportionately. However, the key issue is whether AI will primarily be used for automation, resulting in job cuts and potentially lower wages for displaced workers, or whether it will bring in new goods and services, new business models and new jobs. In the former case, AI is likely to raise the share of capital income, prolonging a four-decade rise in income inequality across most advanced economies. Even in the latter case, skilled professionals working with AI may benefit more than workers in occupations less prone to AI enhancement, which could also worsen income inequality. Policies need to promote an inclusive deployment of AI, by investing in education, promoting reskilling and upskilling in cooperation with the social partners, facilitating job transitions through job search support and career counselling, ensuring fair competition, limiting differences in the tax treatment of labour and capital income, and protecting consumers and citizens from harmful uses of AI.

The views expressed in this column are those of the author and not of the OECD or of its member countries.

AI가 일자리·생산성·불평등에 미치는 영향력

2022년 11월 챗GPT가 출시되자 인공지능(AI)이 여러 분야의 문제 해결에 기여하고 생산성을 높일 수 있을 거라는 큰 기대감이 형성됐다. 그러나 동시에 수많은 일자리가 사라지고 소득 불평등이 심화할 수 있다는 불안감도 퍼져 나갔다. 흔히들 AI를 내연기관이나 초창기의 전기 기반 기술, 컴퓨터와 같은 범용 기술이라고 생각한다. 그런 기술은 경제의 큰 부분을 파괴하고 많은 노동자를 대체할 가능성이 있다. 역사에서 혁신의 물결이 몰려올 때는 어김없이 ‘기술적 실업’에 대한 공포감이 번졌다. 그러나 경제는 때로 고통스러운 전환기를 거치기는 해도 대체로 파괴된 일자리보다 더 많은 일자리를 만들어내곤 했다.

일반적으로 자동화는 생산성을 높이고, 이는 다시 새로운 제품과 서비스에 지출할 수 있는 소득을 창출하며, 결과적으로 노동 수요를 발생시킨다. 자동화하기 어려운 분야의 고용은 총수요와 함께 증가하며 새로운 직업이 탄생하고 있다. 매사추세츠 공과대학교의 데이비드 오터(David Autor)와 공저자들에 따르면 2018년 미국에 존재하는 일자리 중 약 60%가 1940년에는 존재하지 않았다. 기술 변화에 따른 노동력의 재배치는 노동자에게 도전과제다. 재교육(Reskilling)과 숙련도 향상(upskilling)이 필요할 수도 있기 때문이다. 경제가 구조적 변화에 잘 적응하지 못할 경우, 구조적 변화는 거시경제와 금융의 불안정을 동반할 수 있다. 지난 수십 년간 많은 선진국에서 나타난 노동시장의 양극화가 잘 보여주고 있듯이 소득 분배에도 영향을 미친다.

AI 시대의 노동시장 변화는 과거의 패턴을 반복할 것인가, 아니면 인공지능이 게임체인저가 될 것인가? AI를 앞서갔던 많은 디지털 도구가 그랬듯이, AI도 다양한 경제 활동에 활용될 수 있는 엄청난 잠재력이 있다. 최근까지는 주로 정형화된 작업만 자동화가 가능했다. 그러나 AI는 방대한 데이터 세트를 통해 스스로 학습하고 암묵적 지식을 흡수할 수 있어서 비정형화된 인지적 작업도 자동화할 가능성이 있다. 일부 연구자들은 기계가 궁극적으로 거의 모든 활동에서 인간을 능가할 수 있을 거라고 믿는다. 하지만 이 예언을 믿는다 해도, 그 시기는 아마도 먼 미래가 될 것이다. 현 단계에서 AI가 할 수 있는 일은 일부의 인지적 작업을 자동화하고, 좀 더 복잡한 작업을 수행할 때는 인간을 보완하는 정도다.

몇몇 연구는 AI의 일부 적용 사례를 특정 직업에서 사용하는 기술과 연관 지어 다양한 직업군의 AI 노출도를 조사했다. 이것은 AI가 일자리, 생산성, 불평등에 미치는 잠재적 영향력에 대해 생각해 볼 수 있는 좋은 출발점이다. OECD 글로벌 생산성 포럼의 연구에 따르면 금융, 광고, 컨설팅, 정보통신 등 지식 집약적 서비스 분야의 일자리가 AI의 영향을 받을 가능성이 가장 크다. 반대로 광업, 건설 같은 산업이나 행정 및 지원, 운송, 수자원 및 폐기물 등 지식집약도가 비교적 낮은 서비스 분야의 노동자는 AI에 노출될 가능성이 제한적이다. 그 결과, 기술 발전으로 정형화된 업무가 자동화되면 먼저 타격을 받는 것은 주로 블루칼라 노동자들이지만, 그다음에는 지식 집약적인 업무마저 자동화되어 고숙련 노동자의 일자리도 위협받게 될 거라는 우려가 고개를 들고 있다.

관건은 AI의 주된 능력이 업무 자동화인지 아니면 노동자의 업무 수행 능력을 보완할 가능성도 있는지다. 다시 말해, AI의 주된 역할이 인간 노동의 대체인가 아니면 보완인가 하는 것이다. 세계경제포럼의 보고서에 따르면 두 가지 측면 모두 중요하며, 각각이 어느 정도의 힘을 발휘할지는 경제 분야별로 다르다. 모호한 문제를 창의적으로 해결하거나 다른 사람과 실시간으로 협력하거나 결과물을 검증할 필요가 없는 업무는 자동화가 가능하다고 본다. 노동자의 역량을 보완할 가능성은 특히 지식 집약적 서비스 분야에서 높게 나타난다. 예를 들어 정보 및 기술 서비스의 경우, 전체 업무 소요 시간 중 자동화가 가능한 시간은 약 32%지만, 역량 보완 가능성은 전체 업무 소요 시간의 약 37%에 달해 훨씬 더 높았다. 미디어와 출판의 경우, 보완 가능성은 전체 업무 소요 시간의 32%, 자동화 가능성은 24%로, 전자가 후자를 훨씬 크게 압도한다. 따라서 AI가 어떤 노동자들은 대체할 수 있지만, 또 어떤 노동자들에게는 그들의 생산성을 높여줄 수도 있다. 좀 더 구체적인 예를 들자면, AI는 의사의 진단을 개선하거나 법적 증거의 수집에 활용될 수 있지만, 그렇다고 의사와 변호사를 조만간 대체하지는 못할 것이다. AI는 숙련된 전문가에게는 유용한 새 도구가 되겠지만, 중요한 의사 결정을 비롯해 많은 경우 여전히 인간의 개입이 필요하다. 무엇보다 AI가 환각에 빠져 부정확하거나 오해의 소지가 있는 결과를 도출하는 경우가 종종 있기 때문이다.

최근 여러 연구를 보면 AI로 인해 일부 특정 업무에서 노동자의 성과가 크게 개선된 것으로 나타난다. 가령 고객 서비스는 14%, 코딩은 56%다. 이는 AI가 경제 전반에 널리 도입된다면 생산성이 상당히 증가할 수 있음을 시사한다. 그러나 미시적 수준의 성과를 경제 전반의 생산성으로 전환하기는 쉽지 않다. 향후 10년간 선진국에서 AI의 노동 생산성 향상 가능성을 추정한 결과를 보면 대개 연간 약 0.1%포인트(p)에서 2.5%포인트이상까지 수치가 다양하다. 이러한 수치를 좀 더 넓은 맥락에서 살펴보면, 미국의 비농업 분야 노동 생산성은 1947년부터 2023년 사이 연평균 2.1%, 2006년 이후에는 1.5%씩 증가했다. 따라서 가장 낙관적인 추정치를 적용할 경우, AI로 인한 생산성 성장률은 과거 추이를 훨씬 뛰어넘는다. 중간 추정치를 적용하면 노동 생산성 성장률은 인터넷이 보급되던 1996년부터 2005년 사이에 관측된 3%에 근접할 것으로 보인다. 그러나 다른 연구에 따르면 이는 지나치게 낙관적인 전망일 수도 있다. AI와 관련된 생산성 향상은 국가마다 차이가 날 수 있다. 한국은 디지털 발전 수준이 높고 세계 반도체 시장에서 탄탄한 입지를 갖고 있다는 점에서 주된 수혜자가 될 수 있는 여건을 갖추고 있다.

AI의 생산성 효과는 일정 부분 AI의 도입 정도와 속도로 결정될 것이다. 그리고 AI의 도입 정도와 속도는 비용 뿐만 아니라 보완적 요소들을 활용하고 생산 프로세스와 비즈니스 모델을 새롭게 생각할 수 있는 능력에 좌우될 것이다. AI 모델은 개발할 때도 비용이 많이 들지만, 실제 적용할 때도 운영비가 높은 경우가 많다. AI는 에너지 소비가 많은 만큼 지속가능성 목표에 위협이 될 수도 있다. 데이터와 기술 등 보완적 요소의 병목 현상으로 AI의 활용이 제한될 수도 있다. OECD 연구에 따르면 지난 20년간 선두 기업과 다른 기업 간의 생산성 격차는 계속 확대됐다. 빅테크 기업이 데이터, 기술, 컴퓨팅 파워에 대한 접근성을 이용해 디지털 시장의 지배력을 더욱 공고히 할 수 있다면, AI가 이 격차를 더욱 벌려 놓을 수도 있다. 따라서 혁신과 생산성 향상을 촉진하기 위해서는 AI 경쟁을 모니터링하는 것이 필수적이다.

많은 경제학자가 AI가 도입되면서 앞으로 10년간 생산성 수준이 점진적으로 변화할 것으로 예상한다. 한편 가장 낙관적인 경제학자들은 연구의 진척에 가속도가 붙으면서 생산성 증가율이 영구적으로 상승할 것으로 예상한다. 이런 낙관론은 연구 프로세스의 병목 현상을 해결하는 일부 AI 적용 사례가 성공을 거두었다는 사실에 어느 정도 기반을 두고 있다. 예를 들어, 한 AI 시스템은 아미노산 서열을 통해 단백질의 3D 구조를 예측해 생물학과 의학 분야에 큰 가능성을 열어주었다. 그러나 역사적으로 기술 발전은 훨씬 강력한 연구 수단이 등장하더라도 대개 주기적으로 일어났으며 선형적으로 계속되지 않았다. 더구나 과학적 발견을 경제적으로 응용하는 과정은 결코 간단하지 않으며, 종종 기술 외적인 요인에 좌우되곤 한다.

현재의 AI 발전 단계에서 볼 때, 일자리가 대규모로 사라질 거라는 공포감이나 생산성 성장률이 비약적으로 높아질 거라는 기대감은 모두 과장된 듯하다. 그렇지만 AI는 우리의 업무 방식을 변화시키고, 비즈니스 모델과 분배에 영향을 미칠 것이다. 최근 연구에 따르면 AI가 경험이 부족한 노동자의 생산성을 불균형적으로 향상하는 것으로 보이며, 따라서 AI가 도입되면 직업 내 임금 불평등이 감소할 수도 있다고 한다. 그러나 핵심 쟁점은 AI가 주로 자동화에 이용됨으로써 일자리가 줄어들고 대체된 노동자의 임금이 낮아질 것인지, 아니면 AI가 새로운 상품과 서비스, 새로운 비즈니스 모델, 새로운 일자리를 창출할 것인지 하는 문제다. 전자의 경우, AI는 자본소득의 비중을 높여 대다수 선진국에서 지난 40년간 진행된 소득 불평등을 장기화할 가능성이 크다. 후자의 경우에도 AI를 활용하는 숙련된 전문직 종사자가 AI의 발전에 덜 민감한 직종의 노동자보다 더 많은 혜택을 누릴 수 있으며, 이는 소득 불평등을 악화시킬 수 있다. 교육 투자, 사회적 파트너와의 협력을 통한 재교육과 숙련도 향상 지원, 직업 상담과 구직 지원을 통한 직업 전환 촉진, 공정한 경쟁의 보장, 노동소득과 자본소득의 과세 격차 제한, AI의 유해한 사용으로부터 소비자와 시민의 보호 등 AI의 포용적인 활용을 촉진하는 정책이 필요하다.

※ 이 칼럼에 포함된 견해는 OECD 또는 그 회원국의 의견이 아닌 필자의 의견임.

bonsang@heraldcorp.com